The Office Meltdown

Why CRE Is Cracking and What It Means for Regional Banks, SBA 504 Lenders, and the Future of Cities

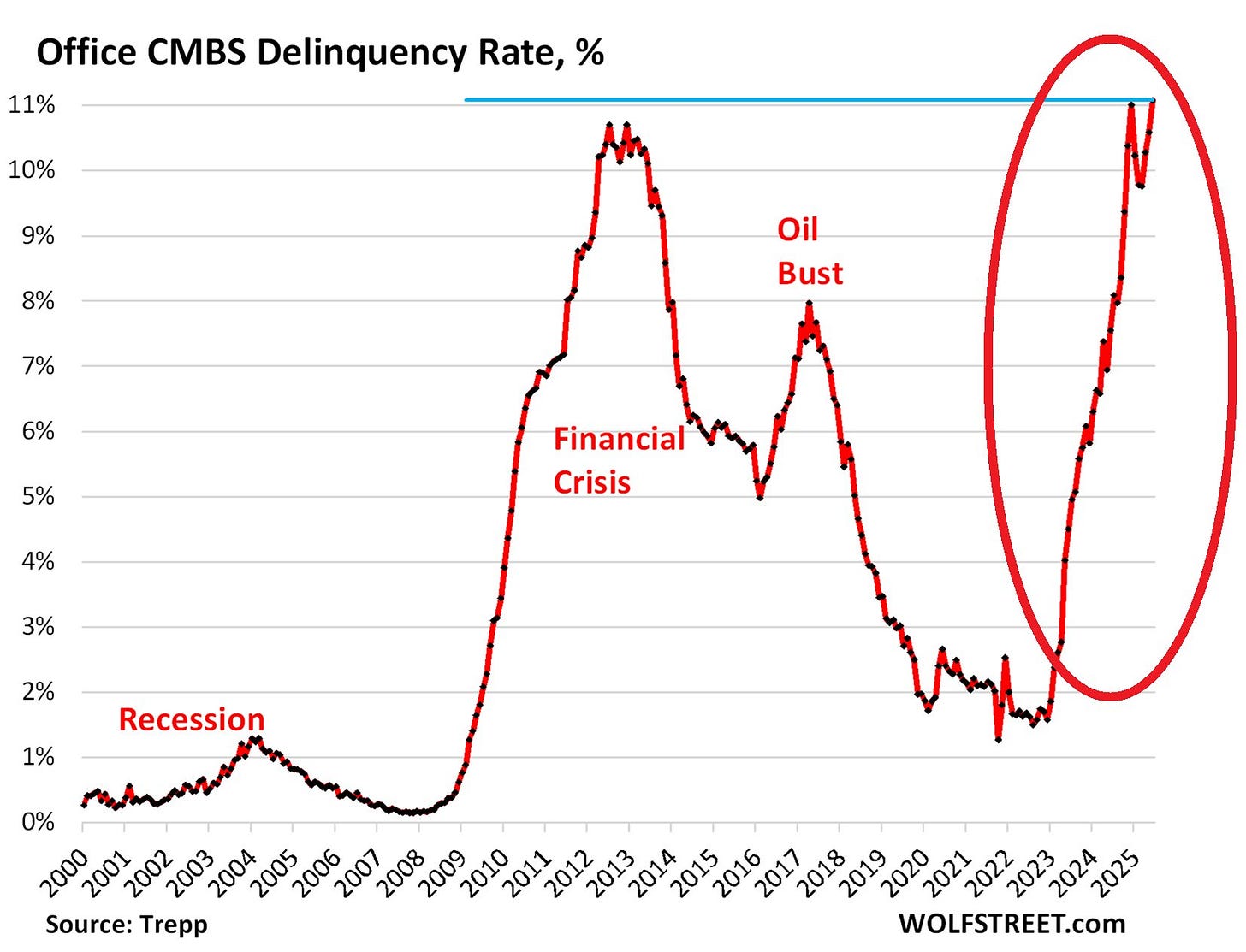

Take one look at the chart and it’s impossible to miss the spike. Office CMBS delinquencies hit 11.1% in June 2025, blowing past the 2008 financial crisis peak of 10.7%. It’s not a blip. It’s a signal—a loud, flashing, unmistakable alarm.

We’re witnessing the slow-motion train wreck of the office sector, a segment of commercial real estate (CRE) that has long propped up urban tax bases, bank portfolios, and economic development strategies. This time, though, the crash isn’t just about bad loans or weak underwriting. It’s about a structural shift. And the fallout? It’s bigger than just empty towers.

Remote Work Is Not a Phase

A 2023 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that demand for office space has dropped 20% permanently post-pandemic. Not temporarily. Not cyclically. Permanently. That’s a generational change.

And yet, much of the office loan underwriting that preceded this shift assumed a world that no longer exists. Leases signed in 2015 don’t matter when tenants downsize or walk away. Vacant floors don’t pay mortgages.

In some markets, office building values have dropped by 50%-70%. With refinancing rates jumping due to the Fed’s 525 basis point hikes from 2022-2023, those drops have turned into defaults. The debt is maturing. The math doesn’t work anymore.

The Delinquency Spiral

Let’s talk about why this spike is different from the one we saw in 2008:

Then, the crisis was driven by financial products—leveraged bets, bundled risk, a collapse in liquidity.

Now, the problem is demand-side. People aren’t going back to the office, and the product—square footage—is obsolete.

Trepp data confirms what lenders have feared for months: the office CMBS delinquency rate jumped by 49 basis points in a single month, hitting 11.1% in June 2025. That’s the worst on record. And there's no bailout coming this time.

A Crumbling Urban Core

This isn't just about banks or landlords. It's about cities.

The Urban Institute reported in 2024 that cities like San Francisco are staring down $1 billion in lost tax revenue by 2028. Property taxes from commercial buildings are a major source of urban funding. When valuations drop, budgets shrink. When vacancies rise, tax receipts fall.

The municipal services that depend on those funds—schools, transit, public safety—aren’t easily replaced. You can’t pave potholes with nostalgia. And if office towers remain half-empty, that revenue gap becomes a structural wound.

What Trump Wants—and Why It Might Not Be Enough

President Trump has been calling for drastic rate cuts, aiming for 1%-2% interest rates, far below the current 4.25%-4.5% range. On paper, that would help. Lower rates mean cheaper refinancing, better valuations, more time to fix the mess.

But here’s the catch: it doesn’t fix the demand problem.

Even if landlords can refinance at lower rates, what happens if tenants still don’t come back? Cheaper debt doesn’t fill empty offices. And the market knows it. That’s why the delinquency rate is still rising.

Lower Rates, Higher Yields? It Can Happen

Normally, rate cuts mean bond yields fall. But not always.

In this scenario, where the Fed cuts rates under political pressure—while inflation remains a threat—long-term bond yields can actually rise. Investors, fearing inflation or deficit spending, demand higher returns.

It’s counterintuitive but real. In late 2024, the 10-year Treasury yield rose after a Fed rate cut. Why? Because the market expected more spending, more inflation, and less discipline.

As of today (July 3, 2025), the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" looks poised to pass, having already cleared the Senate with a 51-50 vote and a House vote underway. This massive piece of legislation—Trump's signature economic initiative—is expected to be signed into law by the 4th of July.

The bill is estimated to add between $3.4 trillion and $3.9 trillion to federal deficits over the next decade. It extends the 2017 tax cuts, boosts defense and immigration spending, cuts Medicaid and SNAP, and slashes clean-energy incentives. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget notes that interest costs alone could exceed $690 billion.

The complexity of the legislation is matched only by its scale. Gross tax cuts total $4.45 trillion, partially offset by nearly $1.5 trillion in spending cuts and nearly $300 billion in spending increases. Despite some fiscal offsets, the result is a net deficit surge. If tariffs are counted, the administration argues that revenue could make up some of the shortfall, but even generous estimates place that figure between $850 billion and $2.8 trillion—far short of closing the gap entirely.

That kind of spending, especially combined with artificially low interest rates, is a recipe for bond market anxiety. If rates fall while borrowing explodes, investors will demand higher long-term yields to offset inflation and debt risks. And that’s what we’re already starting to see.

So yes, the Fed can cut. But that doesn't mean yields will follow. In fact, they may spike—especially if markets expect fiscal chaos.

The SBA 504 Domino Effect

Now, let’s talk about something most people miss: the impact on SBA 504 lenders and regional banks.

504 loans are built on a simple premise—shared risk. A bank takes the senior lien. A Certified Development Company (CDC), like those supported by the SBA, takes a junior piece. Together, they help small businesses buy owner-occupied real estate.

But here’s the problem: if commercial property values fall—and they are—banks get nervous. They worry about collateral coverage. They worry about liquidity. They stop lending.

Even though SBA 504 loans aren’t tied to the office sector directly, the contagion matters. When CRE as a whole comes under pressure, underwriting tightens across the board.

And for regional banks, many of whom have outsized exposure to CRE, this is an existential threat. The Conference Board projected in 2024 that over $1 trillion in CRE loans will mature by 2027. If those can’t be refinanced, we’re talking fire sales, forced write-downs, and potential bank failures.

The Policy Dilemma

So what’s the path forward? There are only bad choices.

Cut rates to 1%-2% as Trump wants, and you may ease the refinancing crunch—but risk reigniting inflation.

Keep rates elevated to fight inflation, and you force CRE defaults that could destabilize regional banks and cities.

Try to do both? Good luck threading that needle.

The Fed is stuck. The Treasury is bloated. And the market is tired of hoping someone else will fix it.

What to Watch

Keep an eye on these three pressure points:

Refinancing Waves: The $2 trillion in maturing CRE debt by 2027 is like a time bomb. If rates stay high, we’ll see a slow bleed. If they fall, we might get a temporary reprieve—but not a cure.

Tax Revenue Gaps: Cities depend on CRE values. As assessments drop, budgets will shrink. That means layoffs, service cuts, and public backlash.

Bond Market Volatility: If the Fed cuts and bond yields spike, it throws a wrench into everything from municipal bonds to private credit pricing.

The End of the Old Playbook

The old playbook—stimulus, rate cuts, wait-it-out optimism—might not work this time. You can’t cut rates enough to make people want to commute. You can’t print tenants.

What we’re seeing now is a structural reset, not just a cycle. That matters for lenders, policymakers, and anyone who cares about the future of cities.

For SBA 504 lenders and regional banks, this means two things:

Opportunity, if you can underwrite wisely in the rubble.

Risk, if you ignore what the chart is screaming.

The storm is here. Whether you sink or swim depends on how seriously you take the warning.

The B:Side Way is about seeing around corners, not just reacting to what’s in front of you. The chart is real. The crisis is real. And the time to adapt is now.