The Private Credit Bubble

Why It Matters for B:Side, SBA Lending, and Regional Banks

There’s been a lot of talk about private credit lately. It’s everywhere—headlines, conference panels, market notes. People are connecting it to the recent collapses at Tricolor and First Brands and wondering if this could be the next weak spot for regional banks.

I know I said I’d stop beating this dead horse, but this one still has some life in it. Private credit matters—to us, to our partner banks, and to the small businesses we serve. So, let’s cut through the noise and talk about what it actually is, why it’s so big, and what it could mean for our world of SBA lending.

What Private Credit Really Is

Private credit is a simple idea with complex consequences. It’s just lending done by non-banks—private equity firms, asset managers, business development companies, and specialized funds that make direct loans to companies. Most of those borrowers are mid-market firms that don’t issue bonds or go to Wall Street. Instead, they sit across a table and negotiate loans privately.

That’s the appeal. The money moves faster. The terms are more flexible. Borrowers like the speed, and lenders like the yield. The loans usually carry floating interest rates, so they adjust as the Fed moves. Everyone wins—until the cycle turns.

The problem isn’t that private credit exists. It’s that it’s grown so fast and so far outside the banking system that we don’t really know where all the risk lives anymore.

By mid-2024, the Federal Reserve estimated the U.S. private credit market at roughly $1.3 trillion. Global estimates are north of $2 trillion. That’s not a niche—it’s a parallel credit universe. After the 2008 financial crisis, new regulations forced banks to pull back on leveraged lending. Private funds filled the gap, and investors searching for yield piled in.

The result? A system that looks and feels a lot like banking but without the same transparency or guardrails. That’s what regulators call shadow banking.

The Shadow Banking System

“Shadow banking” sounds shady, but it’s really just shorthand for lending that happens outside the traditional system. Hedge funds, private-debt funds, and finance companies make loans using investor capital instead of deposits. They take on leverage. They use credit lines. They depend on short-term funding. In many ways, they are banks, just without capital requirements or access to the Federal Reserve’s safety net.

The problem isn’t moral; it’s structural. These players move fast and operate quietly. When they get into trouble, they can’t tap the Fed window or count on deposit insurance. So when something breaks, it breaks hard.

And here’s where it matters to banks: even though these lenders live outside the system, they’re still deeply tied to it. Banks fund them, buy their loans, and hold their securities. So when the shadows stumble, the light flickers too. The Boston Fed recently warned that risk hasn’t disappeared from the banking system…it’s just migrated.

The Warning Shots: Tricolor and First Brands

We got a glimpse of that migration earlier this fall.

In September, Tricolor Holdings filed for Chapter 7. Reports suggested inflated collateral and double-pledged loans. Several banks had exposure, and confidence took a hit.

Then came First Brands Group, a large auto-parts company financed through private credit. Its bankruptcy revealed just how interconnected the system had become. Multiple funds and credit vehicles held slices of the same loans. When it went down, redemptions spiked and credit spreads widened.

It wasn’t just about those two names. It was about what they exposed: inflated valuations, overlapping exposure, and a heavy reliance on leverage. The Bank of England and several U.S. research groups have compared private credit’s structure to pre-2008 subprime lending—high leverage, poor transparency, and deep interconnections.

Zions Bank’s CEO raised a “yellow flag.” Moody’s issued warnings about indirect exposure through warehouse lines and CLOs. These aren’t fringe voices. The people closest to the data are starting to get nervous.

What’s Under the Surface

Most private-credit loans aren’t traded, which means they’re valued internally. In good times, that’s fine. In bad times, it’s dangerous. When markets tighten, “mark-to-model” can quickly turn into “mark-to-make-believe.” True losses show up late, and the lag can make everyone think things are fine, right until they’re not.

Add in rising interest rates, and you have a pressure cooker. Most loans are floating-rate. As the Fed raised rates, borrowers’ interest expenses jumped. Coverage ratios fell. Lenders quietly amended and extended terms to avoid defaults. That’s not a solution: it’s a delay tactic.

Standards also slipped. Covenant-lite loans became the norm. Debt-to-EBITDA ratios crept higher. And some deals were built on growth projections that now look delusional.

The banks? They’re tied in through credit lines, fund financing, and securities purchases. The bridge between the shadow world and the traditional one runs right through the balance sheets of regional banks.

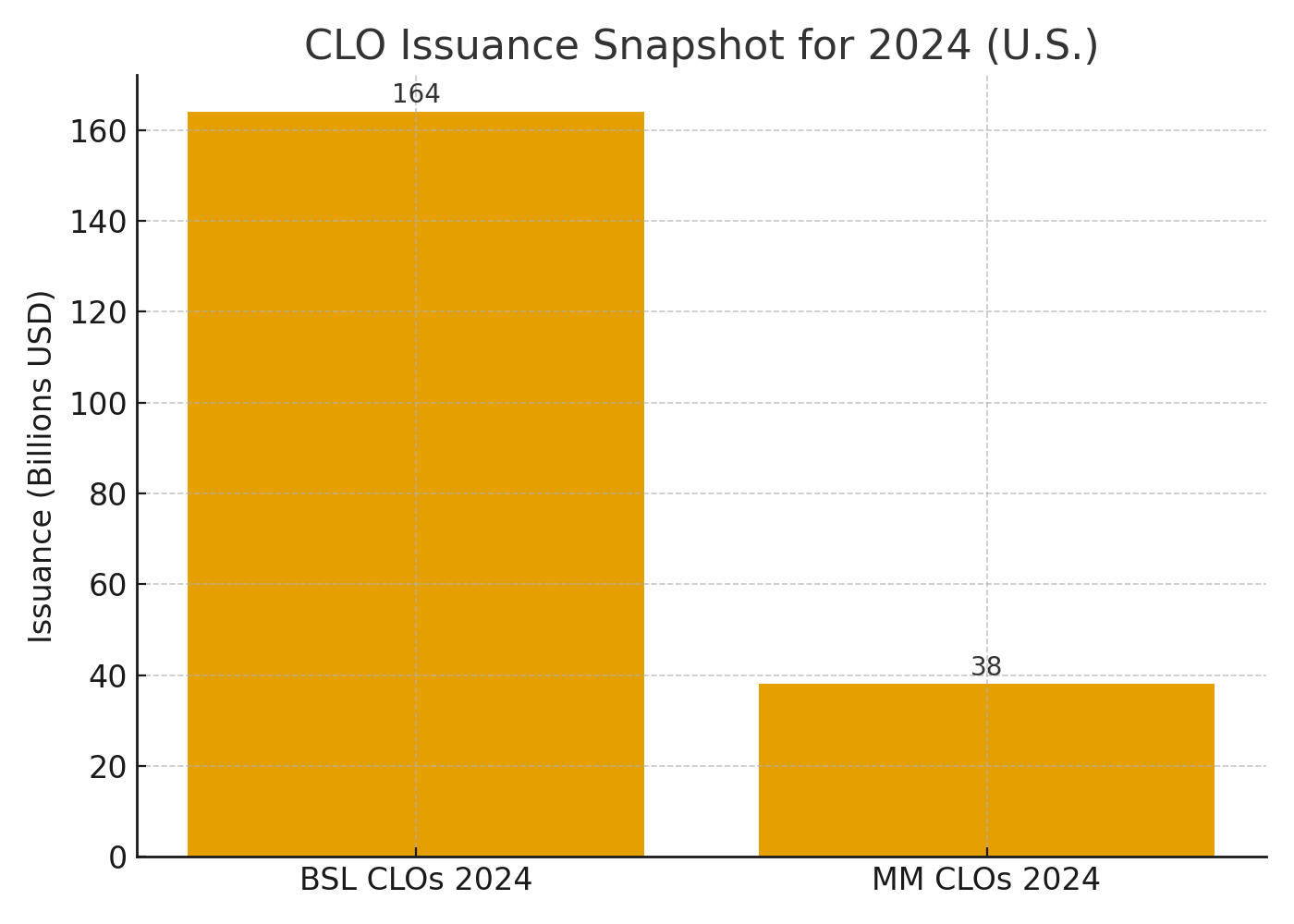

Collateralized Loan Obligations—or CLOs—are the biggest piece of that bridge. These are bundles of loans sliced into tranches of varying risk and return. In 2024, CLO issuance totaled around $200 billion in the U.S. alone, with about $40 billion tied to middle-market private-credit loans. When defaults rise or liquidity dries up, those tranches start to wobble, and the losses ripple outward.

That’s how pressure in the shadows becomes stress in the daylight.

Where We Stand Now

As of late 2025, private credit is still growing. It’s still huge. And it’s still deeply intertwined with the banks that supposedly left this kind of risk behind after 2008.

The Fed’s data suggests direct exposure is modest for now, but the rate of growth is the issue. Fast-moving credit markets tend to hide problems until the cycle turns. Recent research isn’t predicting collapse, but it’s calling loudly for more transparency. The truth is, no one really knows what these assets are worth.

The failures at Tricolor and First Brands weren’t system-shaking events on their own, but they were warning shots. They exposed weak controls, valuation games, and leverage built on leverage. And they reminded everyone that confidence—not capital—is often the real foundation of these markets.

That’s why regional bank executives are paying attention. Confidence can disappear overnight, and when it does, even well-run banks get caught in the downdraft.

What It Means for SBA Lenders and B:Side

When private credit tightens, the businesses caught in the squeeze still need capital. Some will qualify for traditional loans, but many won’t. That’s where SBA lending steps in.

Regional banks with private-credit exposure—through credit lines, CLO holdings, or fund ties—will face pressure. Investors will question them. Regulators will circle back. Funding costs may rise. In that kind of environment, transparent, well-structured loans become a lifeline.

That’s the beauty of SBA programs. A 504 loan with defined collateral, clear cash flow, and a long fixed rate looks nothing like a floating-rate, mark-to-model credit fund deal. It’s simple, it’s transparent, and it’s backed by real assets. When the private market gets jumpy, that’s exactly what banks and business owners want.

For us, that’s not theory—it’s opportunity. When risk moves up the food chain, safety becomes a differentiator. That’s our lane.

How We Should Respond

Stay close to our regional-bank partners. Not to pry, but to help. Ask how they’re feeling about private-credit exposure. Many boards are already worried. If we can help redirect that concern into safe, productive lending channels, we’re adding real value.

Expect more borrowers with bruises. We’ll see balance sheets strained by high rates and overextended credit. Some will come from private credit or leveraged buyouts, and they’ll need help refinancing into fixed, sustainable structures. That’s what we do best.

Expect banks to tighten. Approvals will slow. Credit boxes will narrow. But that only increases demand for SBA lending. The 504 program reduces loss severity and creates liquidity through secondary markets. It helps banks lend when they might otherwise pull back.

Keep educating. Many small-business owners still think “SBA loan” means red tape and delays. We can help them see it for what it really is—a stabilizer that keeps projects moving when the rest of the market is scared.

Rely on Simple Explainers. A one-pager on private credit and shadow banking. A chart showing regional-bank exposures. These visuals make the abstract concrete. They help our partners see what’s coming and how to respond.

The Stock-Price Connection

When investors start to sense risk in private credit, they sell first and think later. The first targets? Regional banks.

Falling stock prices aren’t just bad optics; they change the game. A bank’s stock price signals market confidence in its capital strength. When it drops, investors start assuming losses are coming. That perception alone can raise funding costs as wholesale lenders demand higher spreads.

If the stock stays low, the bank loses flexibility. Raising capital through new shares becomes harder and more dilutive. Mergers get trickier because the math no longer works.

Meanwhile, earnings fall as banks build loan-loss reserves. That drives the stock down further, which reinforces the perception of weakness. The cycle feeds itself.

And there’s a liquidity angle too. When regional-bank stocks tumble, it doesn’t take long for the headlines to spook depositors. Even large corporate accounts that don’t follow bank stocks daily start asking questions. That leads to outflows and higher funding costs. The worse the perception gets, the more it becomes reality.

Supervisors eventually step in. They start asking about contingency plans, capital ratios, and liquidity stress tests. And sometimes, selling assets or raising capital at bad prices turns paper losses into real ones.

That’s the loop we have to watch: fear hits stock prices, which hits funding, which hits lending, which hits earnings, which hits stock prices again.

A solvency problem isn’t just when a bank runs out of money: it’s when the market stops believing it’s safe.

For B:Side and our partners, that means tighter credit, slower approvals, and more scrutiny from boards and regulators. But it also means more banks will be looking for low-volatility lending products, exactly what SBA loans offer.

We can position ourselves as the reliable option when the rest of the market is rattled. That’s not spin. That’s strategy.

What We Can Do Right Now

We don’t have all the answers, and we don’t need to. Our role is to listen, to learn, and to support the people who are closest to the action. The bankers on the front lines see these credit shifts before anyone else. Our job is to understand what they’re seeing and find ways to help.

That starts with more conversations, not presentations. Reach out to our partner banks and ask what they’re experiencing. Are they seeing more stressed borrowers? Are they adjusting their credit appetite or pricing models? Those insights help us respond with empathy and clarity, not theory.

When it makes sense, we can share what we’re learning, whether that’s research, data trends, or practical examples of how SBA structures can help protect margins and reduce risk. Not to teach, but to collaborate.

We can also be a steady voice for small businesses who feel the effects first. Many are facing higher rates, tighter credit, and lenders that have suddenly pulled back. A simple message that says, “If your lender is pausing projects, here are options that still work,” can go a long way. It’s about showing up with solutions, not sales pitches.

And finally, we can quietly track key market signals like private-credit growth, CLO issuance, notable defaults, and regional-bank commentary. A short internal “credit weather check” helps us stay informed and ready, without the noise.

Servant leadership isn’t about predicting the future. It’s about being useful when others are uncertain. That’s what our partners and borrowers need most right now.

The Big Picture

We’re not in the business of calling bubbles. We’re in the business of helping small businesses get real things done. But part of that job is looking around corners. And right now, the corner to watch is private credit.

It’s big. It’s opaque. It’s tied to banks in ways most people don’t see. And it’s already showing cracks.

When markets get nervous, clarity becomes a competitive edge. That’s where we come in. We help banks lend safely. We help small businesses move forward. And we keep the system working when others hesitate.

That’s the work. That’s the opportunity. That’s what B:Side does best.