To Know What Will Happen, Look at What Has

Lessons from Machiavelli for a World in Flux

There’s open conflict between Israel and Iran. Russia’s still grinding away in Ukraine. India and Pakistan keep circling each other. Here at home, things aren’t much better—rising tension, broken trust, and a country that doesn’t feel very united. The economy’s holding on, but just barely. And if you’re anything like me, you’ve probably caught yourself pausing mid-thought, wondering: Where is all this going?

I know I’ve been writing a lot about current events lately. That’s not by accident. I think we’re living through a history-defining moment in time. The pace of change has accelerated. One crisis blends into the next. And for many people—maybe most—it’s overwhelming.

As I write this, it’s about 8:30 p.m. on Sunday evening. By the time this goes live around 8:00 a.m. Monday morning, major developments may have already unfolded. That’s how fast things are moving right now.

There’s a quote often attributed to Lenin:

“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

That’s where we are now. We’re living in one of those weeks.

In times like these, it’s easy to get caught up in the chaos. To react instead of reflect. But if we want to make sense of what’s happening—and prepare for what comes next—we need more than hot takes and headline-chasing.

We need perspective.

Which brings me back to a quote I keep turning over in my mind. It’s from Niccolò Machiavelli, the often-misunderstood thinker from the 16th century:

“Everyone who wants to know what will happen ought to examine what has happened: everything in this world in any epoch has their replicas in antiquity.”

That’s not just poetic. It’s a tool.

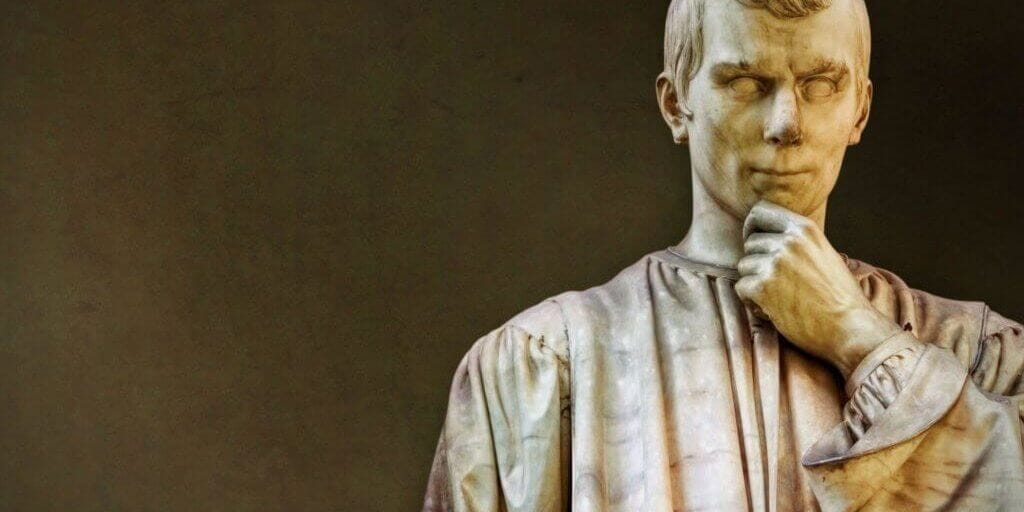

A Simple Truth from a Complicated Man

Machiavelli isn’t easy to summarize. He was born in Florence in 1469, served as a diplomat and senior official in the Florentine Republic, and wrote his most famous work, The Prince, after being kicked out of office, tortured, and exiled. He wasn’t a king. He wasn’t a warrior. He was something more dangerous—an observer. A pattern-recognizer.

While people often think of him as ruthless, that’s mostly the result of cherry-picked quotes and lazy reading. Yes, he wrote about power, manipulation, and force. But he wasn’t telling people to be cruel. He was explaining what he saw in the world—honestly and without apology. If anything, Machiavelli was more realist than cynic. He wanted leaders to see things clearly, not through the rose-colored glasses of virtue or fantasy.

And that’s what makes this quote so powerful.

If you want to know what will happen, look at what already happened.

Why This Matters Now

Let’s step back for a second and look around.

Israel and Iran are trading blows. The U.S. is getting pulled closer to the edge.

Russia’s war in Ukraine drags on, testing the limits of NATO.

Tensions between India and Pakistan keep simmering—two nuclear powers with a long memory.

Inside the U.S., we’re not exactly united. Election season is already bringing out the worst.

The economy? Sure, it’s “fine,” if you don’t squint too hard. But rates are high, debt is rising, and we’re one unexpected shock away from serious pain.

None of this is new. That’s the point.

The names and flags may change, but the underlying forces—power struggles, honor, fear, pride, revenge, greed—stay the same.

History doesn’t repeat, exactly. But it rhymes. The patterns are there, buried under the headlines and talking heads. And if you know where to look, you can start to see how today’s madness fits into yesterday’s stories.

How to See the Pattern: A Quick Framework

Let me walk you through a simple way to interpret events through Machiavelli’s lens. You don’t need a Ph.D. or a stack of old books. You just need a mindset shift and a few tools.

1. Start with First Principles

Strip away the modern context. Forget the specific names or countries for a moment. Ask: What is actually happening here, at its root?

For example:

Israel and Iran? That’s about survival, deterrence, and regional dominance.

Russia and Ukraine? That’s about empire, identity, and pride.

The U.S. domestic unrest? That’s about legitimacy, trust, and control.

All of those are human problems. Ancient problems. You can find echoes of them in Rome, Persia, Athens, Carthage, or the early American republic. Don’t get distracted by the technology or the hashtags. The core issues are timeless.

2. Look for the Archetype

Next, ask: Who is this leader like? What kind of figure are we dealing with?

Is Putin more Caesar or more Napoleon? Is Biden more of a Wilson or a Truman? Is Netanyahu playing Churchill or something closer to Joshua?

This step isn’t about flattery or insults. It’s about identifying the underlying style of leadership. Are they bold and reckless? Calculating and slow? Do they rally people through fear, faith, or force?

Archetypes help you predict behavior. If you know the type, you can anticipate the next move.

3. Zoom Out on the Timeline

Then, expand your view. Ask: Where are we in the cycle?

This is where frameworks like the Fourth Turning can help. But you don’t need a model to get the basic idea. Civilizations move in waves. Peace, then conflict. Order, then decay. Creation, then destruction. And then back again.

In a decaying phase, you’ll see cynicism, polarization, and weakening institutions. In a crisis phase, you’ll see strongmen rise, systems crack, and old norms fall away.

So—where are we now?

My bet? We’re entering the peak of a crisis cycle. Which means things may get worse before they get better. That doesn’t mean we’re doomed. But it does mean we should prepare for more chaos, not less.

4. Ask: What Happened the Last Time?

Now you get specific. Once you know the pattern and the phase, you dig into the past. Ask: When have we seen something like this before? What happened then?

Not because history always plays out the same way, but because it shows you what’s possible—and what traps to avoid.

When two powers compete for control of the Middle East, what usually happens? (See: Rome vs. Parthia, Ottomans vs. Safavids, U.S. vs. USSR.)

When empires overextend and face internal unrest, what comes next? (See: Late-stage Rome, British Empire post-WWI, USSR in the 1980s.)

When inflation and interest rates are high, and debt is unsustainable? (See: Weimar Germany, 1970s America, 1990s Argentina.)

These aren’t perfect parallels. But they help you form a sense of direction. Like landmarks in a foggy landscape.

5. Adapt, Don’t Predict

The final step is a reminder.

This isn’t about calling the exact shot. It’s about range. Possibilities. Contingencies.

Use history to narrow the field. Think in probabilities. If something happened five times in the past under similar conditions, you’d be wise to prepare for it again.

But don’t cling to your forecast like it’s gospel. The world still surprises. Use the past to inform your instincts, not trap them.

Lessons for Leaders

So what do we do with this?

If you’re a leader—in business, in government, in your family—your job is not just to respond. It’s to see around corners.

Here’s what that means in practice:

Don’t overreact to the news. Understand the deeper story. The headlines are often symptoms, not causes.

Train your historical eye. You don’t need to be a scholar. Read biographies. Study the rise and fall of institutions. Watch for themes.

Stay calm, but not passive. Calm isn’t the same as disengaged. Position yourself to move fast when the moment comes.

Watch for moral panic. When societies lose faith in their leaders, they tend to either check out—or lash out. Both are dangerous.

Build antifragile systems. Expect disruption. Design your team, your strategy, and your life so they get stronger under pressure.

Most of all: trust that people have been here before. And made it through. Some stumbled. Some rose. Some burned it all down.

But none of this is new.

One Final Story

There’s a moment I think about often. It’s from The History of the Peloponnesian War, written by Thucydides in 431 BC.

Athens and Sparta were locked in a bitter struggle. The Athenians, confident and wealthy, made a series of strategic mistakes. They overextended, trusted the wrong people, and underestimated their enemies. It didn’t end well.

But what strikes me isn’t the battles. It’s the psychology.

Here’s what Thucydides wrote:

“So little trouble do men take in searching out the truth, so readily do they accept whatever comes first to hand.”

That was 2,500 years ago. He could’ve written it last week.

Which brings us back to Machiavelli.

If you want to know what’s coming, stop scrolling, and start remembering. Look backward—not to live in the past, but to survive the future.

The maps are there. You just have to use them.